|

Many market experts got a big surprise last week. The reason? While they have been forecasting since New Year’s that interest rates would go up, the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury tumbled below 2.5 percent for the first time since Halloween.

The decline in one of the capital markets’ key interest rates didn’t surprise me, though. Regular readers of my Money and Markets columns know that I have been predicting lower interest rates since last summer.

But I am a little worried.

Why are investors continuing to rush into safe-haven U.S. Treasury bonds?

Bond yields are driven down by several factors including inflation expectations, economic growth rates, central bank policies and the threat of global conflicts.

But the primary reason rates have been falling this time is that little or no economic growth means no inflation, which in turn equals lower interest rates.

In last week’s Money and Markets column, I reported Janet Yellen’s recent comment to Congress about the state of the U.S. economy, when she said, “Many Americans who want a job are still unemployed, inflation continues to run below the Fed’s longer-run objectives (of 2 percent) and work remains to further strengthen our financial system.”

And until there is any serious threat of inflation, the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank will continue their easy money policies and be reluctant to hike short-term rates, which have been near zero since the depths of the 2008 financial crisis.

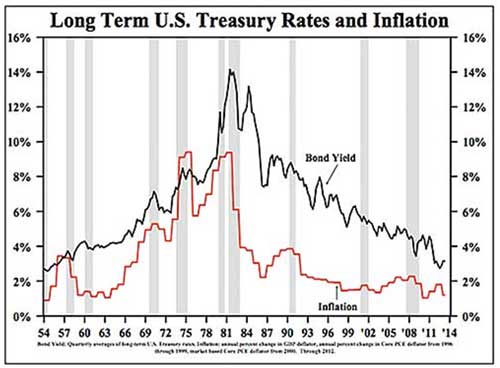

Inflation’s role in setting long-term rates was quantified by Irving Fisher 84 years ago (“The Theory of Interest,” 1930) with the Fisher equation, which says that long-term rates are the sum of inflation expectations and the real rate.

Since then, dozens of historical studies have reaffirmed that proposition. It can also be empirically observed by comparing the Treasury bond yield to the inflation rate, which have moved in the same direction about 80 percent of the time (on an annual basis) since 1954, as shown in the chart below.

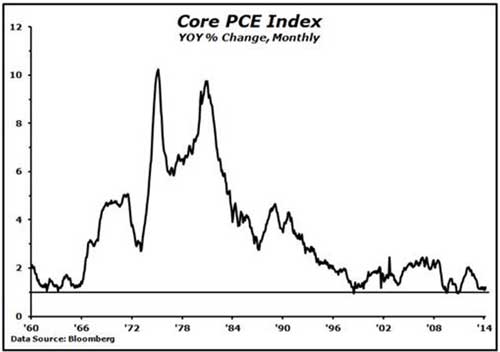

Moreover, the year-over-year change in the core personal consumption expenditures deflator, the primary indicator to which the Fed pays close attention, currently is trending along at levels well below the Fed’s two-percent target.

What’s more, take a look at the chart below, which shows 10-year U.S. Treasury yields compared to 2-year U.S. Treasury yields. As you can see, since the start of this year the trend has been lower, as the 10-year yields have been falling at a faster pace than short-dated yields, even though they are nominally higher.

This is particularly worrisome since an inverted yield curve can be a leading indicator of a recession. The yield curve is telling us that the Treasury market does not believe the recovery will be strong this year, after Q1 GDP rose a measly 0.1 percent. The inverted yield curve could serve as a wake-up call to stock market investors; after all, how high can stocks go when growth is weak?

As I have emphasized, for stocks to go higher and a global economy plagued by excessive debt to make real advances, the world needs economic growth. That’s because growth is the magic elixir that cures all economic ills and propels financial markets higher.

Unfortunately, growth continues to be hard to find, and that is what has caused the recent stock market sell-off and decline in interest rates.

As evidence, take a look at Wal-Mart Stores’ (WMT) earning announcement last week. The world’s largest retailer reported earnings of $1.24 a share on revenues of $116.2 billion. Analysts had been expecting $1.25 on sales of $118.5 billion. Sales in stores open more than a year declined 0.3 percent. Wal-Mart also guided lower for the full year, citing a “challenging sales and operating environment.” As a result, the stock sold off sharply and is at risk of going negative for the last 52 weeks.

But Wal-Mart’s earnings numbers don’t tell the whole story. The retail giant is a barometer for the U.S. economy as a whole. The entire organization is focused on nothing but selling goods and services to the consumer. Wal-Mart sells more than $1 billion worth of merchandise per day in a bad quarter.

Then, on top of Wal-Mart’s earnings miss, the largest department store in the U.S., Macy’s (M), also missed expectations when reporting last week.

For me, when Wal-Mart and Macy’s miss their earnings estimates, it’s a troubling sign that the U.S. economy could be weaker than anyone thought.

From where I sit, it appears as if we are at an economic crossroads. The world and the global stock markets need growth to get going again. Both the Fed and the ECB recognize this fact. Yet, despite both central banks’ easy money policies, growth has been hard to find.

And until there are some signs of growth, inflation and interest rates will remain low and the world’s stock markets will go sideways.

This week, I’m going to be watching Target’s (TGT) earnings report closely to see if the trend of weak U.S. consumer spending continues. I know that I have recently been a proponent of a “risk on regardless” strategy, but for now I recommend that you take a break and sit on the sidelines for a bit with your capital. That way you can see what develops over the next week or so in an environment that remains highly unusual!

Best wishes,

Bill Hall

P.S. Click here to discover the four surprising secrets the world’s wealthiest families use to grow richer … And USE them to grow your wealth in record time!

Bill Hall is the editor of the Safe Money Report. He is a Certified Public Accountant (CPA), Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) and Certified Financial Planner (CFP). Besides his editorial duties with Weiss Research, Bill is the managing director of Plimsoll Mark Capital, a firm that provides financial, tax and investment advice to wealthy families all over the world.

Bill Hall is the editor of the Safe Money Report. He is a Certified Public Accountant (CPA), Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) and Certified Financial Planner (CFP). Besides his editorial duties with Weiss Research, Bill is the managing director of Plimsoll Mark Capital, a firm that provides financial, tax and investment advice to wealthy families all over the world.