|

With markets calm, the economy steady and interest rates near zero, it’s finally time to take big risks, right?

Wrong!

As Mike Larson explains in the upcoming issue of Safe Money Report — and as Larry Edelson warns in his latest video — it’s precisely these kinds of conditions that consistently lead to disaster.

Central banks flood the world with printed money.

Politicians twist the arms of lenders to dish out mortgages to high-risk borrowers.

Investors abandon safe havens and shun defensive strategies.

Consumers overborrow, overspend, exhaust their meager savings, and dive deeply into debt.

Complacency reigns supreme!

This pattern can continue for months. But then, suddenly, the shocks begin to hit like machine-gun fire:

* Prices begin to soar in one particular sector — food, for example. Then, the inflation spreads to gasoline and other commodities … to college tuition and health care … then to wages and nearly all services. Or, alternatively …

* The Fed, seeking to head off an inflationary surge, decides to take a baby step toward sopping up the excess cash in the economy: It raises interest rates. It’s just a tiny move. But in a bubble economy, it’s enough to set off a chain reaction of panicky retreats by investors. Or …

* A small bank goes bust. Next, a medium-size financial institution bites the dust. Soon, the entire nation is enveloped in a bankruptcy crisis of mammoth dimensions.

Sound familiar? It should. Because this is precisely what has happened repeatedly in cycle after cycle since the end of World War II — and with ever-growing intensity.

Each time, the collapse is broader and deeper than the previous. And each time, the Fed steps in with bigger and bigger guns to revive the economy.

For a reality check, go back to the 1960s, for example. Bank lending is still very conservative. So all the Fed has to do is give banks a bit more leeway to make new loans or reduce interest rates a few notches. That’s more than enough to do the trick.

But then fast forward to the early 2000s, and the picture changes dramatically. Even after the Fed cuts interest rates to the lowest level in more than a half century, it still takes many months for the economy to come back.

And look at what’s happened in the most recent cycle:

Even slashing interest rates to nearly ZERO is not enough.

Even holding them near zero for five long years isn’t enough!

In a desperate attempt to revive the economy, the Fed embarks on the greatest and longest money-printing binge of all time.

And the European Central Bank cuts rates BELOW zero (announced on Thursday)!

Yet, despite these herculean efforts, the economy continues to stagnate, with U.S. GDP actually contracting in the first quarter.

What never ceases to amaze me, however, is how little our leaders learn from these repeated experiences.

In Washington and in Brussels, they pat themselves on the back for their “great victory” in “saving” the economy … only to let the bubble pop again after they’ve left office and handed the reins to their successors.

And what’s particularly amazing is how, cycle after cycle, investors gleefully fall for the same great deceptions, over and over again:

Deception #1

I began to tell you about the greatest deception of all last month.

It’s the conflicts, bias, payola, cover-ups and scams behind most Wall Street ratings assigned to hundreds of thousands of companies, bonds, stocks, and investments of all kinds.

And it’s precisely at times like these — when investor complacency is high — that the deceptions are the most rampant.

Here’s the key: If something is overrated, it is overpriced. It attracts buyers that think it’s a good investment. But as soon as the naked truth is revealed or the inflated rating is deeply downgraded, investors run in panic; and the resulting price declines can deliver wipe-out losses.

As I explained last month, this could be one of the greatest silent killers in your portfolio. And whether you use ratings or not, it’s essential that you fully understand how you can avoid the risks.

My experience with this sorry saga begins in the late 1980s. I had been rating the safety of the nation’s banks for over a decade, when I decided to expand our coverage to life and health insurance companies.

Why? Because A.M. Best, Moody’s, S&P and Duff & Phelps (now part of Fitch) were giving out A’s like candy, even to insurers loaded with junk bonds. I gave them D’s.

My reward: A hoard of lawyers on the payroll at major insurers attacked like a pack of well-trained foxhounds. Hundreds threatened lawsuits. Two actually filed in court.

One insurance company executive told us he’d run us out of business with legal costs. Another said “Weiss had better shut the @!%# up or get a bodyguard.”

The ACLI, the lobbying arm of the largest life and health companies, sent personal letters to the chief editors of The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, demanding that they stop quoting me in the press.

Then, even while I was testifying before Congress about the dangers in the insurance industry, ACLI representatives sat in the audience behind my back, passing out anti-Weiss “literature.”

The end result: Within weeks, several giant insurance companies went belly-up just as I’d warned, still boasting high ratings from major Wall Street firms.

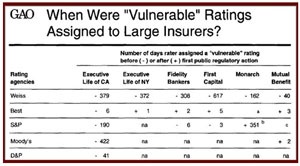

In fact, according to a major study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), in most cases, the established rating agencies didn’t give the companies a warning-level grade until AFTER they went bankrupt. The GAO demonstrates that:

|

| Source: GAO. Click here for entire page ; here for entire report |

* Even after Executive Life of New York failed, A.M. Best, the leading insurance rating agency, didn’t downgrade the company until the next day. (Weiss Ratings had given the company a warning-level grade 372 before it failed.)

* Even after Fidelity Bankers, another major insurer failed, A.M. Best waited two days before it issued its downgrade for the company. (Weiss Ratings had given the company a warning-level grade 308 before it failed.)

* Even after First Capital — also a giant insurer — went under, Best waited FIVE days before downgrading. (Weiss Ratings had warned 617 days before the failure.)

* With Monarch, another huge life insurance company, the GAO reports an even sadder story: S&P didn’t downgrade the company to a warning level until 351 days after it failed. Worse, A.M. Best NEVER publicly recognized Monarch’s failure. Instead, four days after the failure, Best changed its “A” rating for Monarch to a non-published category, effectively slipping out the back door by taking the rating out of circulation. (Weiss Ratings had given the company a warning-level rating 162 days before the failure.)

* And with Mutual Benefit, the story is downright tragic. It was the biggest failure of all, with the largest number of victims and the biggest losses — mostly in speculative real estate. Yet, Moody’s didn’t downgrade until two days after the failure; Best didn’t act until three days after; and S&P never downgraded the company.

The GAO study proved that the only rating agency that predicted all of these failures — and the only one that correctly identified the truly safe companies — was Weiss Ratings. (For the evidence, go here.)

Deception #2

So far, I’ve been talking strictly about insurance company ratings.

But the business of rating common stocks is similar in one critical way: Ratings are often inflated, especially in calm and complacent times like these.

What’s most shocking, however, is how common it has been for Wall Street analysts to continue to lavish praise on a particular stock, even after the company is on the verge of bankruptcy.

To better quantify this shocking trend, my team and I went back to 2002, and we conducted a study on 19 companies that (a) filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the first four months of that year and that (b) were rated by major Wall Street firms.

The result: Among these 19 companies, 12 received a “buy” or “hold” rating from all of the Wall Street firms that rated them.

Furthermore, they continued to receive those unanimously positive ratings right up to the day they filed for bankruptcy.

Thus, even diligent investors who sought second or third opinions on these companies would have run into a stone wall of unanimous “don’t-sell” advice.

Further, we found that, among the 47 Wall Street firms that rated these stocks, virtually all were guilty of the same shenanigans. The Wall Street firms led them like lemmings to the sea, with rarely one dissenting voice in the crowd.

For investors, and for the market as a whole, the consequences were catastrophic …

|

In April 1999, for example, Morgan Stanley Dean Witter stock analyst Mary Meeker — dubbed “Queen of the Internet” by Barron’s — issued a “buy” rating on Priceline.com at $104 per share. Within 21 months, the stock was toast — selling for $1.50.

Investors who heeded Ms. Meeker’s recommendation would have lost 98 percent of their money, turning a $10,000 mountain of cash into a $144 molehill.

Undaunted, Ms. Meeker also issued “buy” ratings on Yahoo, Amazon.com, Drugstore.com, and Homestore.com. The financial media reported the recommendations with a straight face. Then, Yahoo crashed 97 percent; Amazon.com 95 percent; Drugstore.com 99 percent; and Homestore.com 95.5 percent.

Why did Ms. Meeker recommend those dogs in the first place? And why did Ms. Meeker stubbornly stand by her “buy” ratings even as they crashed 20, 50, 70 percent, and, finally, as much as 99 percent?

One reason was because virtually every one of Ms. Meeker’s “strong buys” was paying Ms. Meeker’s employer — Morgan Stanley Dean Witter — to promote its shares, and because Morgan Stanley rewarded Ms. Meeker for the effort with a $15 million paycheck.

While millions of investors lost their shirts, Morgan Stanley Dean Witter and Mary Meeker, as well as the companies they were promoting, cried all the way to the bank.

An isolated case? Not even close! In 1999, Salomon Smith Barney’s top executives received electrifying news: AT&T was planning to take its giant wireless division public, in what would be the largest Initial Public Offering (IPO) in history.

|

Naturally, every brokerage firm on Wall Street wanted to do the underwriting for this once-in-a-lifetime IPO, and for good reason: The fees would amount to millions of dollars. But Salomon had an issue. One of its chief stock analysts, Jack Grubman, had been saying negative things about AT&T for years.

A major problem? Not really. By the time Salomon’s hotshots made their pitch to pick up AT&T’s underwriting business, Grubman had miraculously changed his rating to a “buy.”

More examples:

- Mark Kastan of Credit Suisse First Boston liked Winstar almost as much as Grubman did, issuing and reiterating “buy” ratings until the bitter end. No surprise there: Kastan’s firm owned $511 million in Winstar stock.

- In 2000, an analyst at Goldman Sachs oozed 11 gloriously positive ratings on stocks that subsequently smashed investors’ portfolios. He got paid $20 million for his efforts. One of his best performing recommendations of the year was down 71 percent; his worst was down 99.8 percent.

- Merrill Lynch’s Henry Blodget gained fame by predicting Amazon.com would hit $400 per share. It was soon selling for under $11. Blodget also predicted that Quokka Sports would hit $1,250 a share. It went bankrupt. He issued and reissued strong “buy” ratings for Pets.com (went out of business), eToys (lost 95 percent of its value), InfoSpace (shed 92 percent), and Barnes & Nobel.com (lost 84 percent of its value). Yet even while investors lost billions, Merrill Lynch cleaned up — $100 million on Internet IPOs alone.

In each of these cases, brokerages made millions. The analysts made millions. The companies they promoted raked in millions. But investors lost their shirts.

Not one major firm on Wall Street tied its analysts’ compensation to their actual track record in picking stocks. Analysts could be wrong once, wrong twice, wrong a hundred times, and they’d still earn huge bonuses, as long as they continued to recommend the shares and as long as there were still enough investors who continued to buy into the hype. That’s how the investment banking divisions wanted it, and that’s how it stayed.

What if it was abundantly obvious that a company was going down the tubes? What if an analyst personally turned sour on the company?

Would that make a difference? Not really.

For the once-superhot Internet stock Infospace, Merrill’s official advice was “buy.” Privately, however, in e-mails uncovered in a subsequent investigation, Merrill’s insiders had a very different opinion, writing that Infospace was a “piece of junk.”

Result: Investors who trusted Merrill analysts to give them their honest opinion got clobbered, losing up to 93.5 percent of their money when Infospace crashed.

Merrill’s official advice on another hot stock, Excite@Home, was “accumulate!” Privately, however, Merrill analysts wrote in e-mails that Excite@Home was a “piece of crap.” Result: Investors who trusted Merrill lost up to 99.9 percent of their money when the company went under.

For 24/7 Media, “accumulate!” was also the official Merrill Lynch advice. Merrill’s internal comments were that “24/7 Media is a “piece of s–t.” Result: Investors who relied on Merrill’s advice lost 97.6 percent of their money when 24/7 Media crashed.

Has the payola and bias on Wall Street ended?

Suffice it to say, it comes in waves — in cycles. And as I warned at the outset, the current cycle of complacency does not favor investor vigilance — let alone Wall Street transparency.

Quite to the contrary, it’s the perfect climate for more scams and deceptions.

Don’t get caught. Be sure to invest instead in the best of the best, especially companies that merit a top Weiss Rating.

Good luck and God bless!

Martin

|

EDITOR’S PICKS

These Wall Street Wall Flowers Offer High Quality at a Discount by Don Lucek Is it for real? That was the question I was asking when the S&P 500 kept flirting with the 1,900 mark. Now, with the index notching up one closing record after another and trading solidly in the 1,920s range, I’m becoming a believer What Apple Needs to Do to End Malaise by Jon Markman Apple (AAPL) launched a cynical attempt to gain some attention last week, committing the corporate equivalent of a “selfie,” by confirming at the Code Conference its widely speculated $3 billion acquisition of privately held Beats Electronics. Gold, Silver, Mining Dip: A Bull in Disguise by Larry Edelson Since last week’s plunge, a lot of investors have thrown in the towel on gold, silver and mining shares, yet again. But that’s actually music to my ears. |

THIS WEEK’S TOP STORIES

by Mike Larson In the movie Wall Street, Bud Fox asks Gordon Gekko a simple pair of questions: “How many yachts can you water-ski behind? How much is enough, huh?” I got to wondering the same thing when I came across a pair of Bloomberg stories this morning. Dropping Delusions: Americans Are Growing Poorer by Charles Goyette The abject failure of the policies pursued by the fiscal and monetary authorities for the past seven-and-a-half years keeps getting shoved in our faces. Don’t Ignore These Warning Signs by Bill Hall Successful investing involves focusing on the facts and stats that matter, and disregarding the information that is of no decision-making value. |

{ 3 comments }

You have mentioned very interesting points! ps nice site.

get download http://getblackhatteam.com/get-icpa-profits-are-you-looking-for-a-new-quick-and-easy-way-to-crush-cpa-download/

I have recently started a blog, the information you offer on this website has helped me tremendously. Thank you for all of your time & work.

get blackhat http://getblackhatworld.com/get-6-step-process-to-make-2000-in-7-days-or-less-six-step-process-download/

I truly enjoy reading on this internet site, it has got excellent blog posts. “Don’t put too fine a point to your wit for fear it should get blunted.” by Miguel de Cervantes.

get blackhat http://getblackhatteam.com/get-6-step-process-to-make-2000-in-7-days-or-less-six-step-process-download/