|

What is the “price” of uncertainty? Investors have wrestled with that question for years.

But when it comes to interest rates, the answer is simple: Much more than it is today. And that means rates can — and should — continue to rise for a long time.

I’ve already explained that the jump in interest rates we’ve seen so far is not primarily being driven by fears of surging inflation, fears of out-of-control economic growth or any of the traditional bond-market bugaboos. Instead, it’s due to the inevitable bursting of the third, massive, easy-money-fueled asset bubble over the past decade and a half.

In a recent Money and Markets column, Martin Weiss told you how the Federal Reserve’s insistence on holding interest rates in negative territory (on a “real,” or inflation-adjusted basis) is an incredibly dangerous strategy. After all, the last time the Federal Reserve did so in the 1970s, it led to the biggest interest-rate explosion in U.S. history.

|

| Uncertainty about the future direction of rates and monetary policy is rising, which is why the bull market in rates is nowhere near over. |

Now I want to talk about yet another driver of rising rates — the coming surge in the interest-rate “term premium.”

I don’t want to get too bogged down in bond-market minutiae and jargon. Suffice it to say, the term premium is the “price of uncertainty” — uncertainty about future inflation, economic growth, rate volatility and, in this unique point in history, uncertainty about how the Fed can possibly unwind the most reckless monetary policies the world has ever seen.

Think of it this way: Over the past few years, the Fed has been steadily and consistently buying bonds — trillions of dollars worth. Since investors knew this would continue — they expected rates to stay low forever and foresaw no negative side effects to all the quantitative easing (QE) — they went along for the ride. The combination of the Fed’s and private market players’ buying consistently drove down the term premium.

Now, there are several ways to measure the term premium. Different techniques give you somewhat different results. But the general direction and conclusion of almost all models is basically the same.

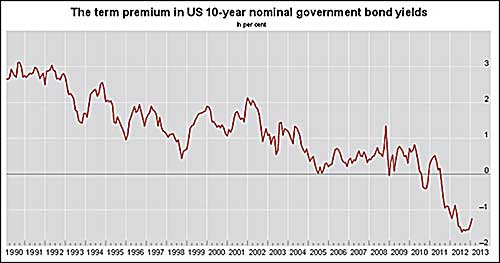

With that in mind, take a look at this chart showing Bloomberg’s relatively conservative term premium estimate:

The data go back all the way to the mid-1970s, and you can see that what happened in the past couple of years is unprecedented. The term premium had never been as low as it was in 2011-2013, a testament to the magnitude of the bond-market bubble the Fed inflated.

Just to get back to “normal,” according to Bloomberg’s (conservative) model, long-term interest rates would have to be about a half percentage point higher than they are now. And in past rate “shocks,” the premium surged much higher. Rates would have to be roughly a percentage point and a half higher than they are now, assuming a mid-1990s-style rate shock, and a hefty 2 1/2 percentage points higher, assuming an early-1980s-style bond-market collapse.

But, again, that’s using Bloomberg’s model. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) — the “central bank to central banks” based in Switzerland — is much more concerned.

According to its model, the term premium collapsed to negative 140 basis points (1.4 percentage points) in December 2012. That compared to an average in the late 1990s of positive 140 points. In the early 1990s, it was even higher — between 250 and 300 points — as you can see in this chart:

Do you see why the interest-rate math is so scary here?

In December 2012, with the term premium at minus 140 basis points, 10-year Treasuries were yielding just 1.6 percent. To get from negative 140 points to the late-’90s average of positive 140 points, you’d need a 280-point surge in yields. That’s a move from 1.6 percent to 4.4 percent. Considering we are still only around 2.75 percent today, that’s a lot more room to run.

But wait a minute. To get to an early-1990s-style premium of 300 points, you’d have to tack on another 160 points. That would put 10-year yields at 6 percent — more than double their current level.

Or as the BIS explained in the February 2013 report that contained its conclusions:

“Even a return to the very moderate risk premia observed during the 2000s — that is, neither a shock to inflation expectations nor a shock to expected real interest rates — would suffice to entail a substantial rise in yields. Recall the 1994 bond market crisis discussed in section 4: it was not primarily caused by changes in macroeconomic fundamentals.”

Long story short? Sure, interest rates can make some short-term zigs and zags, depending on economic growth and inflation. But the big picture is clear: Uncertainty about the future direction of rates and monetary policy is rising, and along with it, so should the “price of uncertainty.” That is yet another reason why I believe the bull market in rates is nowhere near over.

Until next time,

Mike