|

Alice laughed. “There’s no use trying,” she said: “one can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

Similar to the White Queen in Through the Looking Glass, the Federal Reserve has begun believing in impossible things in an attempt to invigorate a stubbornly slow U.S. economy.

To understand what I mean, you have to look no further than the Fed’s belief in the so-called “wealth effect.” In a nutshell, the wealth effect is supposedly a boost in consumer spending that occurs because of an increase in consumer wealth. With consumer spending accounting for almost 70 percent of U.S. GDP, it’s understandable why the Fed has focused its policies on the consumer.

Indeed, former Fed Chair Bernanke said it this way in an opinion column for The Washington Post on Nov. 5, 2010: “Higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion.”

|

| Janet Yellen, like Ben Bernanke before her, continues to believe in the impossible. |

Following Bernanke’s lead, current FOMC Chair Janet Yellen said this in the Jan. 20, 2014 issue of Time magazine: “And part of the [economic stimulus] comes through higher house and stock prices, which causes people with homes and stocks to spend more, which causes jobs to be created throughout the economy and income to go up throughout the economy.”

The problem is that the wealth effect — if it exists at all — is not working.

And as a result, the Fed has been continuously overly optimistic regarding its expectations for economic growth in the United States since the financial crisis ended in 2009. If the Fed’s annual forecasts had been realized over the past four years, then at the end of 2013 the U.S. economy would have been approximately $1 trillion larger, and many of our current economic woes and corporate earnings concerns would be behind us.

So where was the wealth effect in 2013?

If the wealth effect was as powerful as the Fed believes, consumer spending should have turned in a stellar performance last year. Recall that since their lows posted almost five years ago, stocks have risen an amazing 170 percent.

And in 2013 alone, the stock and housing markets posted large gains. Highly regarded bond manager Hoisington Investment Management Company reports that on a yearly average basis, the real-inflation-adjusted stock market index, as measured by the S&P 500, increased in 2013 by a whopping 17.7 percent, and the real-inflation-adjusted Case Shiller Home Price Index posted a strong 9.1 percent gain as well.

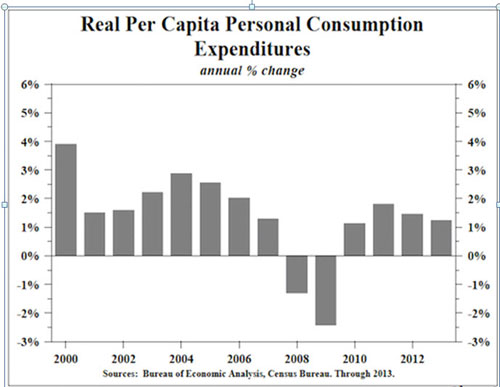

The combined increase in these wealth proxies of 26.8 percent was the eighth-largest gain in the 84 years of data collection. Yet, real per capita personal consumption expenditures (PCE) gained just 1.2 percent, which ranked a weak 58th out of the 84 years. What’s more, the difference between the increase in stock market and housing wealth as measured against the increase in PCE was the fifth-largest of the 84 observations!

What does all of this mean?

Put simply, it means that 2013’s eye-popping stock market returns and solid housing price gains did not translate into any meaningful increase in consumer spending as reported in the chart below. Such a huge discrepancy in economic performance, occurring as it did in the fourth year of an economic expansion, raises serious doubts about the reality of the wealth effect.

Remember that since the Fed began its QE policies in 2009, its balance sheet has increased by more than $3 trillion. While this balance sheet expansion may very well have saved the financial system from crashing and caused overall wealth (as measured by stock and house prices) to surge, it’s obvious that the U.S. economy has received no meaningful boost. As economist Chris Low says, “There may not be a wealth effect at all. If there is a wealth effect, it is very difficult to pin down …”

What’s more, just like the White Queen in Through the Looking-Glass, the Fed has no idea what the ultimate outcome of further increases will be or what a return to a ‘normal’ balance sheet might look like.

As I pointed out in a previous Money and Markets column, for stocks to go higher, it’s time for the world’s leading companies to show some real, honest-to-goodness earnings growth led by top-line sales increases. But in a debt-laden world where the consumer is struggling, growth is hard to find.

That’s why stock prices have been relatively flat so far this year. There has been no sign of any sustainable earnings growth.

Rest assured that normal monetary conditions are not coming back anytime soon, because the Fed remains concerned that normalization would blow away any hope for corporate growth prospects.

That’s why I continue to believe that, for now, it’s “risk on regardless,” but earnings need to come through for stocks to make any significant upward progress.

Best wishes,

Bill

P.S. Did you catch Mike Larson’s Monday afternoon column about what Bank of America’s gigantic stumble could mean for shareholders? If you missed it, click here.

Bill Hall is the editor of the Safe Money Report. He is a Certified Public Accountant (CPA), Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) and Certified Financial Planner (CFP). Besides his editorial duties with Weiss Research, Bill is the managing director of Plimsoll Mark Capital, a firm that provides financial, tax and investment advice to wealthy families all over the world.

Bill Hall is the editor of the Safe Money Report. He is a Certified Public Accountant (CPA), Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) and Certified Financial Planner (CFP). Besides his editorial duties with Weiss Research, Bill is the managing director of Plimsoll Mark Capital, a firm that provides financial, tax and investment advice to wealthy families all over the world.

{ 1 comment }

Everyone knows that China should be moving to more consumer spending and the U.S.,to less.China is doing that,but the U.S.,as usual,doesn't want to take the pain,involved in the transition.We couldn't even adopt the metric system,during the 70's.What a country.