|

A broad swath of the market has reeled in the past three weeks following a bombardment of weak earnings reports on Wall Street, a wipeout of commodity prices in the farm belt and painful reminders of global instability abroad.

Yet having this information in our memory bank now does not necessarily help much. The reason, as the Geico Insurance commercial refrain suggests, is that “Everybody knows that.”

The most common mistake that investors make, in fact, is in extrapolating their most immediate experience into the future. The behavioral scientists call this the “recency effect.” Basically, if you got kicked in the teeth as an investor yesterday, you expect to be kicked in the teeth tomorrow.

Yet markets tend to swing from one extreme to another, so just as soon as you get used to one regime, another one may be already queued up — ready to surprise you.

In this context, I would suggest there are two developments that have the potential to surprise the majority at risk. The first would be a sizeable rebound from recent losses, and the second would be the start of a truly bearish cycle once the immediate pressure is relieved. Nobody knows the future with any certainty, of course, but these are the high-probability paths that my research has identified.

Unless there are very unusual conditions, sessions like last Thursday — when the Dow Jones Industrials lost more than 300 points in a single day — typically lead to the transfer of shares from weak hands to strong hands. That’s kind of a cliche, but it means that people without conviction about their stocks end up selling them willy-nilly, and the buyers at fire-sale prices are people who have a lot more knowledge about their value. You could say that shares move from the public at low prices to the smart money at funds who then hold for gains — though over the years I have learned there is a lot of dumb money at institutions too.

This is the kind of situation that calls for an analysis by Jason Goepfert, who is a master analyst of sentiment data. He reports that the last time we witnessed such an abrupt change in fortunes was in April 2013.

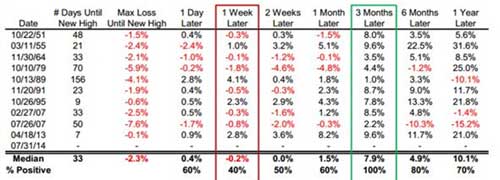

The basic conditions: The S&P 500 was sitting at a three-year high barely a week ago, and now the index has dropped to at least a 30-day low. The table below shows the index’s returns going forward in these circumstances in the past.

As you can see, the normal reaction was shorter-term selling pressure, as one week later the S&P 500 was weaker than average.

But by three months later, every occurrence sported a positive return, and one that was significantly above what we saw during any random three-month period. Actually, we didn’t have to wait three months — even two months later (not shown in the table), every occurrence was positive, averaging a gain of 4.8 percent, according to Gopefert’s analysis.

It took a median of 33 trading days and an additional 2.3 percent loss before the S&P 500 closed at a fresh multi-year high. It took as little as seven days and as long as 156, but there was a good cluster between 20 to 70 days.

When Goepfert relaxes the parameters to look for times when the S&P 500 had set a multi-year high within two weeks instead of just one week, we get 28 occurrences. Three months later, the S&P 500 was positive 26 times (a 93 percent win rate), averaging a 6.2 percent gain.

Bottom line: Mini-shock weeks like the one just witnessed have been fairly consistent in leading to short-term negative follow-through, then intermediate-term positive returns. This analysis makes a lot of sense and comports with other studies I have done. It leads me to believe that we should keep our powder dry now and lay plans to buy techs, health care and cyclicals in the coming week.

However, after the indexes put in a decent-sized rebound, I would be looking to batten down the hatches as generally speaking the metrics that I study suggest that the market is quite overbought and expensive on a broad scale that is in line with past peaks.

I realize there are 50 analysts who will tell you that valuations are fine and the economy is perking along. But the research that I use peers under the hood of both valuations and momentum in a unique way, and has been quite predictive in the past, including 2007 and 2000. It is not perfect, and there is always the chance that the overbought condition will be relieved by stocks going sideways instead of down — which would be my preferred path.

One of the groups that I look at for clues is consumer discretionary, and particularly retailers that specialize in children. It is always disturbing to see teenager-focused retailers suffer the way Aeropostale (ARO), American Eagle Outfitters (AEO) and Abercrombie & Fitch (ANF) have of late, as that market has been a classic “canary in a coal mine” to understand the broader retail trends. Just like canaries die of constricted oxygen supply before humans, teen retailers become asphyxiated from lower spending levels before stores catering to adults. An emphatic, persistent turn higher in these three would be welcome news indeed — but is pretty unlikely at this point, srsly.

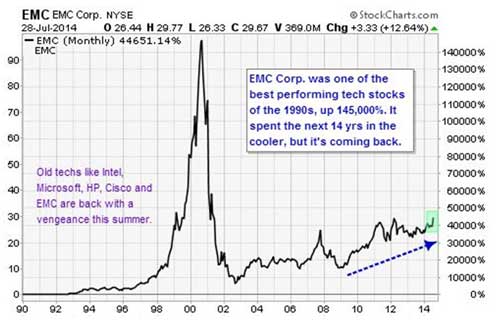

In the technology area, which is my specialty, I have been very impressed by the performance of many of the old guard of late — i.e. Microsoft, Intel, Hewlett Packard, Xerox, Cisco and EMC. All of these stocks were blasted for 60-90 percent losses in the past decade but have been storming back this year as their valuations finally reached levels that attracted the smarter value investors. These are likely to persist in their outperformance in coming months, as the least is expected of them.

Best wishes,

Jon Markman

P.S. The techs I follow aren’t flaky, fly-by-night companies or risky pie-in-the-sky, no-earnings crapshoots. Yet they are the companies I feel are destined to be the Amazons, Apples and Microsofts of the 21st Century. For my list of five red-hot technology stocks to check out now, click here.